Scoliosis is a condition characterized by an abnormal curvature of the spine. It affects millions of people worldwide, with varying degrees of severity. While most cases of scoliosis are structural, meaning that the curvature is caused by a structural abnormality in the spine, there is also a subset of scoliosis known as non-structural scoliosis. Non-structural scoliosis, also referred to as functional scoliosis, is a temporary curvature of the spine that is not caused by a structural abnormality. In this article, we will explore the distinguishing features of non-structural scoliosis, including its causes, symptoms, diagnostic methods, treatment options, and long-term outlook.

Understanding Scoliosis: A Brief Overview

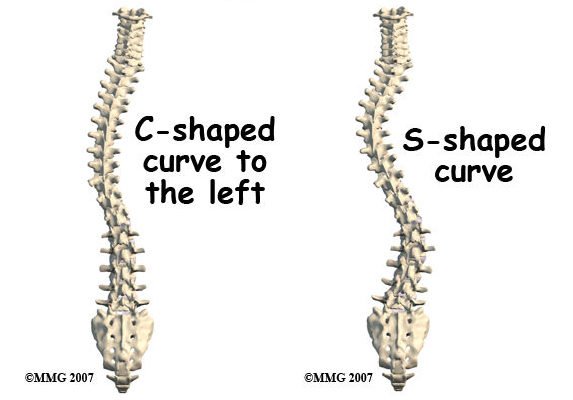

Before delving into non-structural scoliosis, it is important to have a basic understanding of scoliosis as a whole. Scoliosis is a three-dimensional deformity of the spine, characterized by a sideways curvature. It can occur in any part of the spine, including the cervical (neck), thoracic (mid-back), and lumbar (lower back) regions. The curvature can be either “C-shaped” or “S-shaped,” and its severity can range from mild to severe.

Differentiating Between Structural and Non Structural Scoliosis

The key difference between structural and non-structural scoliosis lies in the underlying cause of the curvature. Structural scoliosis is caused by a structural abnormality in the spine, such as a rotated vertebra or a malformed disc. This type of scoliosis is typically permanent and requires medical intervention. On the other hand, non-structural scoliosis is a temporary curvature of the spine that is not caused by a structural abnormality. Instead, it is often the result of muscle imbalances, leg length discrepancies, or other external factors. Non-structural scoliosis can often be corrected through non-surgical approaches and does not typically require long-term treatment.

Causes and Risk Factors of Non Structural Scoliosis

Non-structural scoliosis can be caused by a variety of factors. One common cause is muscle imbalances, where certain muscles in the back are stronger or tighter than others, leading to an imbalance in the spine. This can be the result of poor posture, muscle weakness, or repetitive movements. Leg length discrepancies can also contribute to non-structural scoliosis. When one leg is shorter than the other, it can cause the pelvis to tilt, leading to a curvature of the spine. Other risk factors for non-structural scoliosis include certain sports or activities that put excessive strain on the spine, such as gymnastics or weightlifting.

Signs and Symptoms of Non Structural Scoliosis

The signs and symptoms of non-structural scoliosis can vary depending on the severity of the curvature. In mild cases, there may be no noticeable symptoms, or the symptoms may be subtle and easily overlooked. However, as the curvature becomes more pronounced, symptoms may include uneven shoulders or hips, a visible curvature of the spine, muscle imbalances or tightness, and back pain or discomfort. It is important to note that non-structural scoliosis is typically not associated with neurological symptoms, such as numbness or weakness in the limbs.

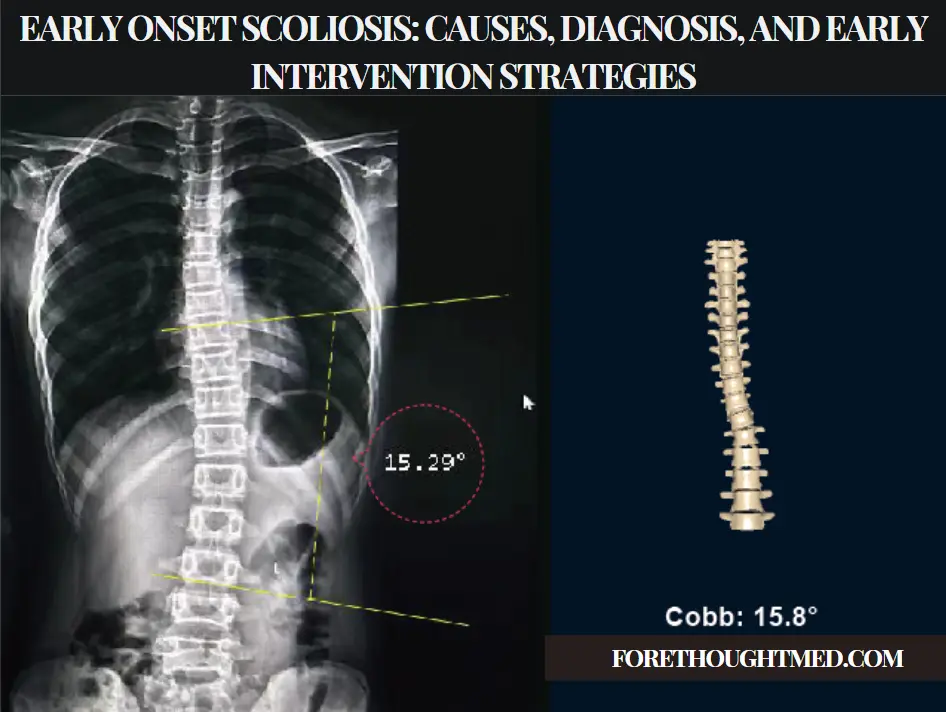

Diagnostic Methods for Non Structural Scoliosis

Diagnosing non-structural scoliosis typically involves a thorough physical examination and medical history review. The healthcare provider will assess the patient’s posture, range of motion, and muscle strength. They may also perform a leg length measurement to check for discrepancies. X-rays may be ordered to rule out any structural abnormalities and to determine the severity of the curvature. In some cases, additional imaging tests, such as an MRI or CT scan, may be necessary to further evaluate the spine.

Treatment Options for Non Structural Scoliosis

The treatment options for non-structural scoliosis depend on the severity of the curvature and the underlying cause. In mild cases, conservative approaches may be sufficient to correct the curvature and alleviate symptoms. These approaches may include physical therapy, chiropractic care, and bracing. Physical therapy can help strengthen weak muscles, improve posture, and increase flexibility. Chiropractic care focuses on spinal adjustments to restore proper alignment and reduce muscle imbalances. Bracing may be recommended for children and adolescents with moderate curvature to prevent further progression.

Non-Surgical Approaches for Managing Non Structural Scoliosis

Non-surgical approaches are often the first line of treatment for non-structural scoliosis. Physical therapy plays a crucial role in managing the condition by addressing muscle imbalances, improving posture, and increasing core strength. Physical therapists may use a combination of exercises, stretches, and manual therapy techniques to achieve these goals. They may also provide education on proper body mechanics and ergonomics to prevent further strain on the spine. In addition to physical therapy, other non-surgical approaches for managing non-structural scoliosis may include chiropractic care, massage therapy, and acupuncture.

Surgical Interventions for Non Structural Scoliosis

In rare cases, surgical intervention may be necessary for non-structural scoliosis. This is typically reserved for severe cases where conservative approaches have failed to correct the curvature or alleviate symptoms. The goal of surgery is to straighten the spine and stabilize it using rods, screws, or other hardware. The specific surgical technique used will depend on the individual’s unique circumstances and the surgeon’s expertise. It is important to note that surgery is typically considered a last resort and is only recommended when the benefits outweigh the risks.

Rehabilitation and Physical Therapy for Non-Structural Scoliosis

After surgical intervention for non-structural scoliosis, rehabilitation and physical therapy play a crucial role in the recovery process. Physical therapists will work closely with the patient to restore strength, flexibility, and function. They will develop a personalized treatment plan that may include exercises, stretches, and manual therapy techniques. The goal of rehabilitation is to help the patient regain mobility, reduce pain, and improve overall quality of life. Physical therapy may continue for several months or even years, depending on the individual’s progress and specific needs.

Long-Term Outlook and Prognosis for Non Structural Scoliosis

The long-term outlook for non-structural scoliosis is generally positive, especially with early intervention and appropriate treatment. With conservative approaches, such as physical therapy and chiropractic care, many individuals are able to correct the curvature and manage their symptoms effectively. However, it is important to note that non-structural scoliosis can be a recurring condition, especially if the underlying causes are not addressed. Regular follow-up appointments with healthcare providers and adherence to recommended treatment plans are essential for long-term management and prevention of recurrence.

Conclusion: Living with Non Structural Scoliosis

Living with non-structural scoliosis can be challenging, but with the right treatment and support, individuals can lead fulfilling lives. It is important to seek early intervention and appropriate treatment to prevent the progression of the curvature and alleviate symptoms. Physical therapy, chiropractic care, and other non-surgical approaches can play a crucial role in managing non-structural scoliosis and improving overall quality of life. By addressing muscle imbalances, improving posture, and increasing core strength, individuals can regain mobility, reduce pain, and prevent further complications. With proper care and management, individuals with non-structural scoliosis can thrive and enjoy an active lifestyle.

References

- Qiu Y, Zhu F, Wang WJ, et al. “Radiological classification and risk factors for curve progression in idiopathic scoliosis.” European Spine Journal. 2008;17(9):1327-1339. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0702-3.

- Weiss HR, Lehnert-Schroth C, Moramarco M. “Non-surgical treatment of scoliosis: The Schroth method and its application.” Physical Therapy. 2008;88(6):703-712. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20070204.

- Watanabe K, Hosogane N, Toyama Y, et al. “Optimal treatment strategy for non-structural scoliosis in children and adolescents.” Asian Spine Journal. 2011;5(2):132-139. doi: 10.4184/asj.2011.5.2.132.

- Hawes MC, O’Brien JP. “A treatment approach for non-structural scoliosis: Combining chiropractic and physical therapy techniques.” Chiropractic & Manual Therapies. 2006;14:25. doi: 10.1186/2045-709X-14-25.

- Negrini S, Donzelli S, Aulisa AG, et al. “2016 SOSORT guidelines: Orthopaedic and rehabilitation treatment of idiopathic scoliosis during growth.” Scoliosis and Spinal Disorders. 2018;13:3. doi: 10.1186/s13013-018-0175-8.

- Monticone M, Ambrosini E, Cazzaniga D, et al. “Active self-correction and task-oriented exercises reduce spinal deformity and improve quality of life in subjects with mild adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: Results of a randomized controlled trial.” European Spine Journal. 2016;25(10):3118-3127. doi: 10.1007/s00586-016-4625-4.

- Romano M, Minozzi S, Zaina F, et al. “Exercises for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;8. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007837.pub2.

- Kuru T, Yeldan İ, Dereli EE, et al. “The efficacy of three-dimensional Schroth exercises in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A randomised controlled clinical trial.” Clinical Rehabilitation. 2016;30(2):181-190. doi: 10.1177/0269215515575745.

- Bettany-Saltikov J, Weiss HR, Chockalingam N, et al. “Surgical versus non-surgical interventions in people with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis.” Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(4). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010663.pub2.

- Weinstein SL, Dolan LA, Cheng JC, et al. “Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis.” Lancet. 2008;371(9623):1527-1537. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60658-3.