Early Onset Scoliosis Definition

Understanding Early Onset Scoliosis Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis is typically diagnosed in children aged 10 to 15. Detecting idiopathic scoliosis in infancy or early childhood is uncommon. The classification of scoliosis types is generally based on the age of initial diagnosis:

- Infantile idiopathic scoliosis: from birth to 3 years old

- Juvenile idiopathic scoliosis: from 3 to 8 years old

- Early-onset idiopathic scoliosis, inclusive of both infantile and juvenile scoliosis, spans from birth to 8 years old.

Causes of Early Onset scoliosis

Early-onset scoliosis, although considered a subtype of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, lacks a identified cause. In contrast to idiopathic scoliosis, which may manifest as an isolated spinal condition, early-onset scoliosis frequently presents alongside additional health challenges. These may include chest wall deformities, neuromuscular conditions like spina bifida or cerebral palsy, and other elements such as both benign and malignant spinal tumors. Due to the intricate nature of early-onset scoliosis and its association with diverse health issues, comprehensive care necessitates the expertise of clinicians who are part of a multidisciplinary team. This team should possess significant experience in addressing all facets of this rare disorder.

Indicators and Manifestations of Early Onset Scoliosis

Asymmetrical shoulders, displaying a noticeable tilt, with one shoulder blade projecting more prominently than the other

Noticeable prominence of the ribs on a specific side

Irregular contour of the waistline, displaying unevenness

Discrepancy in hip height or positioning

Overall visual impression of leaning to one side

Early Onset Scoliosis Treatment

Some children with early-onset scoliosis do not require treatment; their condition may not worsen or may correct itself as they grow. Other children with progressive curves may need immediate treatment to prevent chest wall deformity and allow normal lung development. Close monitoring of all children with early-onset scoliosis can determine which treatment path is best for each individual child.

Non-Surgical Scoliosis Interventions

Some patients with early-onset scoliosis do well without surgery and may only need to be monitored regularly by a physician to ensure the curve doesn’t worsen. Monitoring may include regular observation, X-rays and lab tests.

The brace will reduce pressure on your child’s lower back and help prevent worsening of the curvature in the spine. It should be worn most of the time (16-20 hours a day) for optimal results.

Back bracing may also be recommended as a medical aid leading up to or immediately after spine surgery.

Body Casting for Early-Onset Scoliosis

Serial body casting may also be recommended. This is often chosen for children between the ages of 6 months and 6 years with X-ray measurements that suggest that her curve will worsen. Unlike a brace, the cast has the potential to partially or completely straighten the curve. Other times, when correcting the curve is not possible, the cast treatment can be used to delay the need for implant surgery.

Surgical Scoliosis Interventions

For children with spinal curves of 40 degrees or greater, spinal surgery is almost always indicated.

Doctors will determine which surgery is right for your child depending on your child’s age, skeletal maturity and other health considerations. Each child is evaluated individually, and treatment is suggested based on his long-term health needs.

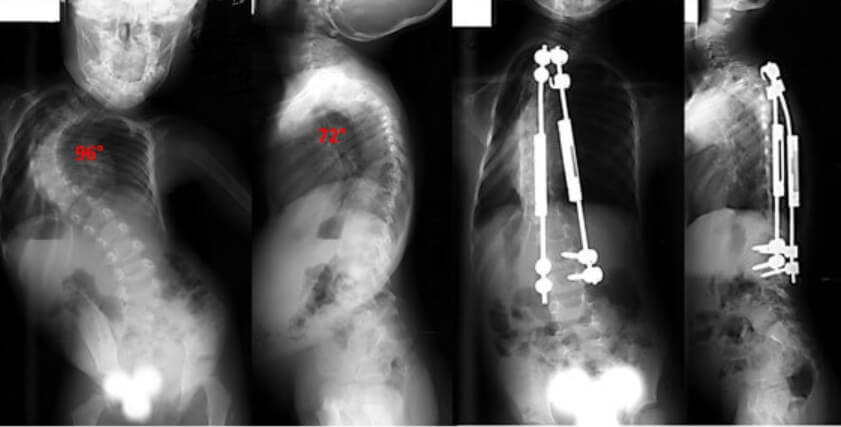

Growing rods

For children who have many years of growth remaining, a growth-friendly option is preferred. In growing rod surgery, the curve in your child’s back is spanned by one or two rods under the skin to avoid damaging the growth tissue of the spine. The rods are attached to your child’s spine and vertebrae above and below the curve. The growing rods help guide spinal growth and drive the spine straight.

As child grows, he will return to the Hospital every six months for outpatient surgery to have the growing rods expanded. This approach minimizes the spinal deformity, maximizes spine growth and allows continued lung development as the child grows.Spinal fusion

During a spinal fusion surgery, the abnormal curved spinal bones are realigned and fused together. Metal implants are also inserted to correct the curvature.

Spinal fusion will effectively stop the growth of the child’s spine, which is why the procedure is generally not recommended as an initial treatment for early-onset scoliosis in younger children.

The results of spinal fusion are much more positive if the surgery is performed after your child has reached skeletal maturity. For adolescents who have achieved normal lung capacity before scoliosis curves worsened, spinal fusion can improve their quality of life and life expectancy.

Early Onset Scoliosis Screening in Forethought

Forethought stands out in the early-onset scoliosis screening domain with its dedication to innovative and portable medical devices. The company’s robust research and development team, comprised of experts in medical research, clinical medicine, electrical engineering, algorithmic research, and medical rehabilitation, showcases cutting-edge capabilities. Forethought Medical excels in smart optical sensing, precise terrain scanning, multi-sensor data fusion, and digital twin technologies. Their pioneering products, the “Forethought Spinal Data Collection & Analysis System” and “Sapling Spinal Detector,” revolutionize spinal detection, offering simplicity and portability in advancing healthcare technology.

References

- [1] Weinstein SL, Dolan LA, Cheng JC, et al. “Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis.” Lancet. 2008;371(9623):1527-1537. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60658-3.

- [2] Negrini S, Donzelli S, Aulisa AG, et al. “2016 SOSORT guidelines: Orthopaedic and rehabilitation treatment of idiopathic scoliosis during growth.” Scoliosis and Spinal Disorders. 2018;13:3. doi: 10.1186/s13013-018-0175-8.

- [3] Asher MA, Burton DC. “Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: natural history and long-term treatment effects.” Scoliosis. 2006;1:2. doi: 10.1186/1748-7161-1-2.

- [4] Lenke LG, Betz RR, Haher TR, et al. “Multicenter evaluation of spinal growth rates in children with idiopathic scoliosis.” Spine. 1998;23(5):593-600. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199803010-00015.

- [5] Dobbs MB, Weinstein SL. “Infantile and juvenile scoliosis.” Orthop Clin North Am. 1999;30(3):347-360. doi: 10.1016/s0030-5898(05)70086-4.

- [6] Sanders JO, Browne RH, McConnell SJ, et al. “Maturity assessment and curve progression in girls with idiopathic scoliosis.” Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2007;89(1):64-73. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00004.

- [7] Kotwicki T, Negrini S, Grivas TB, et al. “Methodology of evaluation of scoliosis, back deformities and posture.” Scoliosis. 2009;4:26. doi: 10.1186/1748-7161-4-26.

- [8] Glassman SD, Berven S, Kostuik J, et al. “Scoliosis Research Society Instrument Validation Study: A Multicenter Assessment of Surgical Outcomes in Idiopathic Scoliosis.” Spine. 2005;30(6):699-702. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000157447.56975.3e.

- [9] Kaspiris A, Grivas TB, Weiss HR, Turnbull D. “Scoliosis: Review of diagnosis and treatment.” International Journal of Orthopaedics. 2013;37(1):34-42. doi: 10.1038/s41390-020-1047-9.

- [10] Negrini S, Hresko TM, O’Brien JP, et al. “Recommendations for research studies on treatment of idiopathic scoliosis: Consensus 2014 between SOSORT and SRS Non-Operative Management Committee.” Scoliosis and Spinal Disorders. 2015;10:8. doi: 10.1186/s13013-015-0032-4.

- [11] Ohrt-Nissen S, Dahl B, Gehrchen M. “Surgical treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: 2-year postoperative radiographic and clinical outcome in 125 consecutive patients.” European Spine Journal. 2016;25(10):3362-3368. doi: 10.1007/s00586-016-4541-7.

- [12] Schlosser TPC, van der Heijden GJMG, Versteeg AL, et al. “Scoliosis during pubertal growth: Spontaneous evolution and predictive factors.” European Spine Journal. 2014;23(12):2625-2631. doi: 10.1007/s00586-014-3594-8.

- [13] Pialasse JP, Simoneau M, Lemay M, et al. “Postural stability and sensorimotor adaptations in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis.” Gait & Posture. 2016;50:40-45. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2016.08.016.

- [14] Bettany-Saltikov J, Weiss HR, Chockalingam N, et al. “Surgical versus non-surgical interventions in people with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis.” Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(4). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010663.pub2.

- [15] Negrini S, Donzelli S, Aulisa AG, et al. “2016 SOSORT guidelines: Orthopaedic and rehabilitation treatment of idiopathic scoliosis during growth.” Scoliosis and Spinal Disorders. 2018;13:3. doi: 10.1186/s13013-018-0175-8.